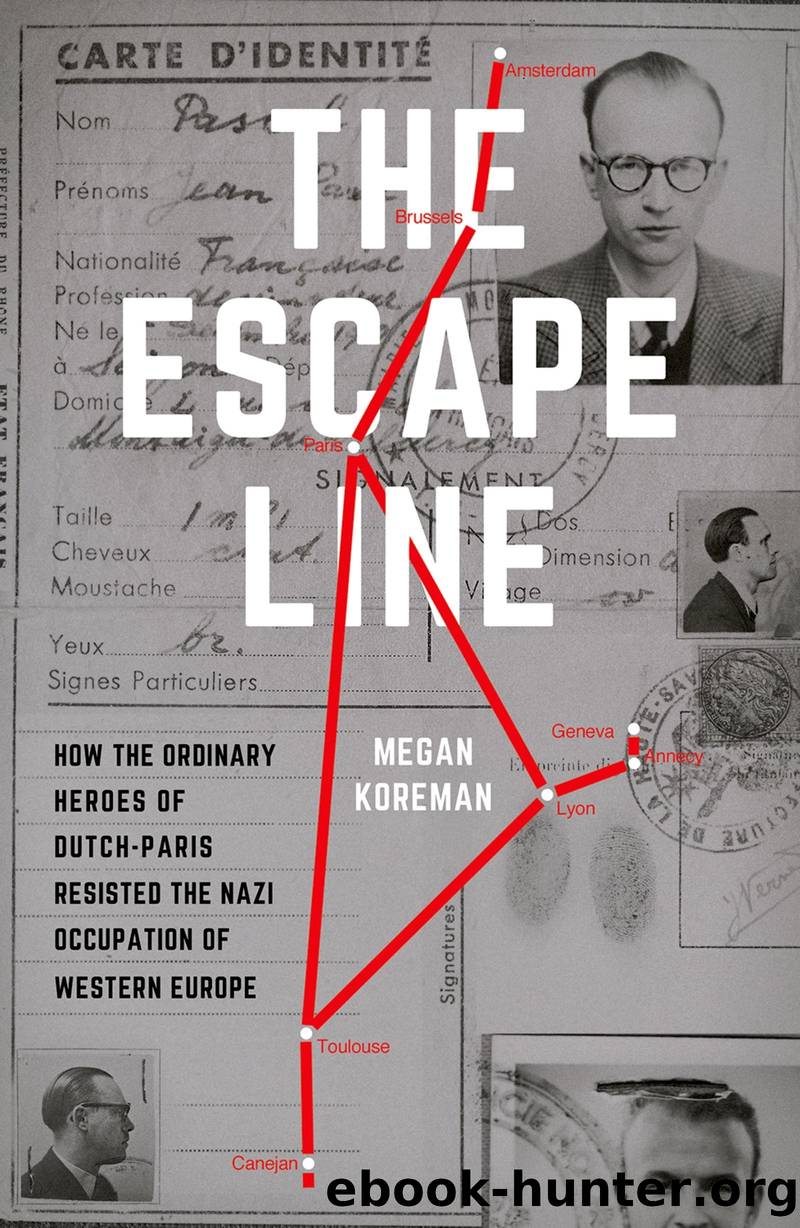

The Escape Line by Megan Koreman

Author:Megan Koreman [Koreman, Megan]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780190662301

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2018-03-13T00:00:00+00:00

Gare Matabiau, Toulouse, France, 1950.

8

Sociaalwerk in the Chaos of War

The loss of so many helpers and reliable addresses in February and March 1944 hampered but did not end Dutch-Parisâs illegal work. The Germans who supervised the roll-up of Dutch-Paris, particularly the Abwehr counterespionage officer Richard Christmann, were primarily interested in stopping Allied airmen from evading capture. They appear to have limited their investigation to the escape lines to Spain and to Switzerland. Dutch-Parisâs own security measures that separated the transportwerk from the Swiss Way microfilm relay and the sociaalwerk also limited the damage. Weidner and his colleagues continued to assist those in hiding and deliver documents. The only thing Dutch-Paris stopped doing altogether in March 1944 was escort Allied airmen from Brussels or Paris to Spain.

Nonetheless almost everyone based in Paris had been captured, including Nijkerk and those he had recruited to help him rebuild the line there. In Brussels most of the young people who had done the daily work of rescue had been arrested, as had the men and women who bore the daily responsibilities for the line in Lyon and Annecy. Dutch-Parisâs leadersâJean Weidner, Jacques Rens, and Edmond Chaitâwould have to both restructure certain aspects of their illegal work and recruit more helpers to make up for these losses. They themselves took on even more responsibility and travel than before. They needed to keep moving in any case because they had no way of knowing what information the Germans might have tortured out of their prisoners. They did know that Weidner had a price on his head: 5 million French francs, as Pillot remembered it; 1 million according to Weidner himself.1 Either one counted as a small fortune.

At the same time as the men and women of Dutch-Paris reorganized the network, the battle was returning to western Europe. Despite German censorship, people in the occupied territories knew that the Soviets had been inflicting heavy losses on the Wehrmacht and pushing it back toward the German homeland since their crushing victory at Stalingrad in February 1943. They knew the Allies had landed in Italy in September 1943. In late 1943 and early 1944 a civilian on the ground in the Netherlands and Belgium could see hundreds of bombers heading toward Germany at a single time. Towns that were not officially in the warzone, such as Paris, Maastricht, Toulouse, and Annecy, suffered aerial bombardment, sometimes by mistake. Occupied and occupier alike expected an Allied invasion somewhere in western Europe in 1944.

These signs of the Third Reichâs weakness emboldened the armed resistance. Partisans sabotaged trains, roads, and bridges and assaulted collaborators. Such attacks made the German occupation forces and their collaborators more anxious and more likely to commit the kind of atrocities they had previously confined to the East. Indeed the Haute-Savoie had been in a state of civil war between the resistance Armée Sècrete and the collaborationist Milice and occupation forces since January 1944.2 Rens had changed his travel plans because of the tensions in Annecy as early as December 1943.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Phoenicians among Others: Why Migrants Mattered in the Ancient Mediterranean by Denise Demetriou(594)

american english file 1 student book 3rd edition by Unknown(585)

Verus Israel: Study of the Relations Between Christians and Jews in the Roman Empire, AD 135-425 by Marcel Simon(584)

Caesar Rules: The Emperor in the Changing Roman World (c. 50 BC â AD 565) by Olivier Hekster(568)

Basic japanese A grammar and workbook by Unknown(550)

Europe, Strategy and Armed Forces by Sven Biscop Jo Coelmont(511)

Give Me Liberty, Seventh Edition by Foner Eric & DuVal Kathleen & McGirr Lisa(485)

Banned in the U.S.A. : A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries by Herbert N. Foerstel(479)

The Roman World 44 BC-AD 180 by Martin Goodman(469)

Reading Colonial Japan by Mason Michele;Lee Helen;(462)

DS001-THE MAN OF BRONZE by J.R.A(456)

The Dangerous Life and Ideas of Diogenes the Cynic by Jean-Manuel Roubineau(449)

Introducing Christian Ethics by Samuel Wells and Ben Quash with Rebekah Eklund(446)

The Oxford History of World War II by Richard Overy(444)

Imperial Rome AD 193 - 284 by Ando Clifford(443)

Catiline by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(412)

Literary Mathematics by Michael Gavin;(406)

Language Hacking Mandarin by Benny Lewis & Dr. Licheng Gu(399)

Brand by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(376)